|

|

The Gig Economy, Ride-Hailing and Sharecroppers

10/24/2020

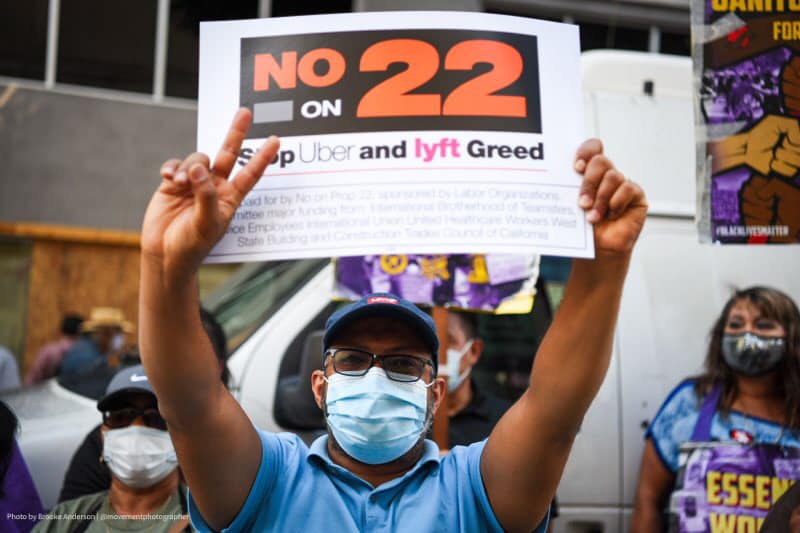

Gig economy companies have aggressively asserted that these workers are independent contractors, and therefore not covered by labor protections for employees, an argument that the California Supreme Court has explicitly rejected. Proposition 22 would classify their drivers as independent contractors. But rejecting gig workers’ employee status particularly harms communities of color. Black Americans are especially more likely to engage in gig work that requires physical tasks (such as ride-hailing) and to rely on gig work as a main source of income. The attacks against gig economy workers’ employee status are not only being waged in California, but also at the federal level. The Department of Labor issued a proposed rule on September 22, 2020, which would change the way that the Labor Department determines whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor. Most notably, the proposed rule would replace the Fair Labor Standards Act’s previous interpretations of employee versus independent contractor status, particularly the FLSA’s past interpretation for tenants and sharecroppers. Sharecropping, an institution in the Southern United States that began after the abolition of slavery and lasted well into the 1940s and ‘50s, was another manifestation of abuse of Black labor. Black workers toiled on White-owned land while enduring lower wages and brutal work conditions. Loans for essentials such as food, tools, and seeds from White landowners that could only be paid for by the sharecropper’s and tenant farmer’s crops led to a nearly unbreakable cycle of indebtedness. The FLSA makes it clear that sharecroppers and tenant farmers were not just independent contractors working on someone’s land, but were employees that had employee rights. The FLSA - -and most rulings on employment status by other agencies -- use the “economic-realities” test, which examines five factors that holistically analyze the nature of a person's work to decide whether that worker is an employee or independent contractor. The Labor Department’s recent proposal would make two of those five factors count more than the other three: i) the nature and degree of the individual’s control over the work, and (ii) the individual’s opportunity for profit or loss. The other three factors, which would count less under the new rule, are (iii) the level of investment (e.g., buying tools) required by the worker, (iv) whether the work requires special skill and initiative by the worker, and (v) whether the relationship between the worker and employer is permanent or indefinite. While this rule change may seem innocuous, it actually represents a pretty blatant attempt by lobbyists for the gig economy companies to be able to classify their workers as independent contractors. Independent contractors do not have a right to a minimum wage or any other benefits or work protections.  Under the Labor Department’s new rule, gig workers will be seen as independent contractors due to their ability to control their work duration and location, and their ability to make a profit due to these controls. But, the rule fails to compute another important aspect in many gig workers' jobs: that they have no control over data and the applications that control their work. Ride-hailing drivers can control the location and duration of their work, but the companies they work for control their access to data about their riders. Are they really independent contractors if their access to customers (and therefore profit) is fully controlled by the company they work for? Just as sharecroppers were ruled to be employees because they did not own the land they worked on nor did they control farm operations, so too should app-based drivers be deemed employees. Companies that rely on app-based drivers own the land (apps) that ride-hailing drivers and other app-based workers rely on. Denying gig workers employee benefits and rights due to a false assertion that they are independent contractors is the way ride-hailing companies (and others taking advantage of gig workers) abuse misconceptions about technology to save money. As the fight for labor rights for agricultural workers and all workers continues, we must also protect gig economy workers. If you’re a California voter, you can support ride-hailing drivers’ fight for employment status by voting no on Proposition 22 on November 3. Prop. 22, officially the App-Based Drivers as Contractors and Labor Policies Initiative, would exempt companies that use app-based drivers from using the standard set by California’s Supreme Court and codified by the legislature in a law known as AB5 that protects gig workers, including app-based drivers. If Prop. 22 passes, app-based drivers would be labeled contractors instead of employees, denying them crucial worker benefits and protections. You can read more about ride-hailing drivers’ fight for employment status and fight against Proposition 22 on the Gig Workers Rising! website. We must address the rapid changes and harms that technology companies and innovations present so that all people, particularly communities of color and low-income communities, are not only protected, but uplifted.

Serena Oduro is Greenlining’s Technology Equity Fellow. Back To News |

|